Gain new perspectives for faster progress directly to your inbox.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid designed for fast-acting pain relief up to 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin. Due to its relatively low cost, fentanyl is frequently mixed with other substances including heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine. Yet even a small amount of fentanyl can be fatal, resulting in unintentional overdoses. Since 2015, fentanyl and its analogs have become the leading cause of drug-related fatalities in the United States.

Fentanyl has become a major public health crisis. According to the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee using the CDC’s methodology, the economic impact of the opioid crisis was an estimated $1.5 trillion in 2020. This includes treatment, prevention, and law enforcement. However, new scientific advances can help reduce future deaths by creating better pain relievers, reducing side effects, and developing vaccines.

The respiratory impact of fentanyl

At the most basic level, fentanyl works by binding to a group of opioid receptors, µOR, in the brain. These receptors are responsible for pain perception, mood, and breathing. When fentanyl binds to these receptors, it can cause several effects, including euphoria, confusion, and sedation, but the most dangerous ones are respiratory depression and arrest, unconsciousness, coma, and death.

The lethal dose of fentanyl (2mg) is so small that, in its powder form, the appearance is smaller than a pencil tip. Even more alarming is carfentanil (a dangerous analog derived from fentanyl), which is 100 times more powerful and only requires 0.02 mg (the equivalent of a few grains of salt) to be deadly.

| Opioid drug | Lethal Dose | Comparative Visual |

| Heroin | 30-100* mg | small bead |

| Fentanyl | 2 mg | Pencil tip |

| Carfentanil | 0.02 mg | Grains of salt |

*Lethal amounts can vary due to physiological make-up, duration of use, and additional substances

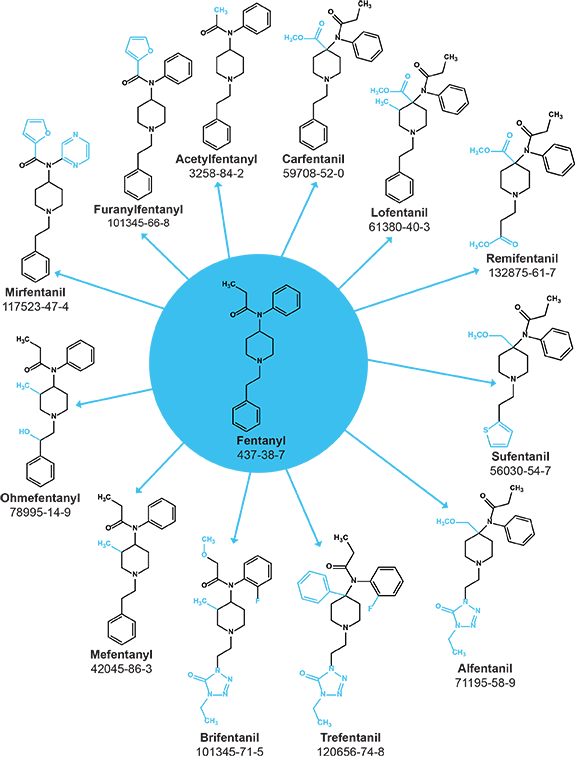

Cheap and easily derived analogs create challenges

Fentanyl has a relatively low cost of production (~$1000 per kilogram) but it has a high street value of about $50,000-$110,000. This makes it a very profitable drug for criminals to sell. Fentanyl is also very easy to mix with other drugs, such as heroin and cocaine, which may make them more potent and addictive.

To avoid detection by authorities, drug dealers often synthesize fentanyl analogs. These drugs are chemically similar to fentanyl, but with slightly different structures. This makes them harder to identify and track.

More than 1,400 fentanyl analogs have been reported in scientific literature. This makes it very difficult for law enforcement to keep up with the latest trends in fentanyl production.

Fentanyl analogs are highly potent opioids that are often used in illicit drugs. There are about 42 analogs of fentanyl that are listed as controlled substances. These include alfentanil (CAS RN®. 71195-58-9), which is 600 times more potent than morphine, and carfentanil (CAS RN. 59708-52-0), which is 10,000 times more potent than morphine. Other common analogs of fentanyl that can lead to illicit drug overdose include acetylfentanyl, butyrfentanyl, and furanyl fentanyl. Carfentanil is responsible for the highest number of deaths.

Naloxone, today’s treatment for overdoses

When fentanyl is ingested or transmitted, the best course of action to prevent an overdose is with naloxone, (commercially known as Narcan) which is now available in either injectable or nasal sprays under a variety of commercial names. This recently approved over-the-counter drug can rapidly reverse fentanyl or another opioid overdose. Typically, an overdose usually causes sedation, decreasing the respiratory rate and increasing respiratory acidosis (inability of lungs to expel carbon dioxide). Naloxone replaces fentanyl or its analogs by attaching to the same neurological receptors (i.e., µOR), reversing the effect of fentanyl in less than five minutes. Unlike morphine, a nearly 10-fold greater dose of naloxone is required to reverse the effects of fentanyl fully.

Future vaccinations could prevent overdoses

- Naloxone is a drug that can reverse opioid overdoses. However, it has two challenges:

- It needs to be administered by someone who is aware that the victim is overdosing. It needs to be administered as soon as possible after the overdose.

Creating a vaccine could help prevent overdoses before they happen. Recently, scientists have made significant progress in developing vaccines for opioid use disorders. These vaccines are designed by coupling a hapten that resembles the targeted opioid structurally (fentanyl, morphine, etc.) with a carrier protein capable of eliciting an immunological response.

The antibodies produced by administering opioid-specific vaccines act by trapping the ingested opioid and preventing it from reaching the central nervous system (CNS) and other organs. This allows the body to avoid the activation of reward pathways and the development of dependence on the drug. A potentially attractive benefit of opioid vaccines is the longer duration of action conferred by antibodies over other opioid treatment options such as naltrexone depot injections, which could result in better patient compliance.

Monovalent and bivalent opioid vaccines against fentanyl, carfentanil, and combinations such as carfentanil/fentanyl, heroin/fentanyl, and heroin/oxycodone are being actively researched. These vaccines can be a more proactive solution that could be administered to at-risk individuals, healthcare workers, and first responders.

Reducing the side effects of future pain relievers

In the United States, fentanyl is involved in more youth drug deaths than heroin, meth, cocaine, benzos, and Rx drugs combined. The development of safer opioids that reduce the risk of respiratory depression is critical. Advances in our understanding of the binding pockets, structural information, and downstream signaling of key opioid receptors may enable the development of safer opioids and reduce the unwanted side effects.

Binding pockets could reduce respiratory impact

It has long been speculated that fentanyl and its analogs differ from morphine and other µOR agonists’ ability to recruit distinct downstream signaling molecules. This ability, referred to as biased signaling, was thought to be the reason behind the increased potency of adverse effects associated with fentanyl and its analogs.

Computational studies revealed that the flexible fentanyl molecule could assume a binding pose in the binding pocket of µOR that the rigid and bulky morphinan analogs could not. Historically, limited structural information about the interactions of fentanyl at µOR was available.

This recently changed when a group of researchers used cryo-electron microscopy to determine the structure of µOR bound to fentanyl and morphine (Figure 2B). The analysis of those structures revealed that fentanyl used a secondary binding pocket near the orthosteric site that morphine was unable to use. The ability of fentanyl to cause respiratory depression was shown to be linked to the conformational changes that it induced in µOR, allowing the recruitment of β-arrestin. β-arrestin is a signaling protein whose activation may lead to respiratory depression.

Functional selectivity from downstream signals

A growing body of research shows that different opioids can have different effects on the body, even though they act on the same receptor. This is called functional selectivity. For example, the opioid lofentanil is more likely to cause respiratory depression than the opioid mitragynine pseudoindoxyl. This is because lofentanil preferentially activates downstream signaling pathways that are involved in respiratory depression, while mitragynine pseudoindoxyl preferentially activates downstream signaling pathways that are involved in pain relief. This newly discovered information about functional selectivity can be used to develop new opioids that are more effective at pain relief and less likely to cause dangerous side effects.

Looking ahead

In recent years, there has been a growing focus on prevention efforts to reduce the number of opioid overdoses. These efforts include public education campaigns, naloxone distribution programs, and law enforcement initiatives to target the supply of opioids. The federal government has also invested heavily in prevention efforts. The White House’s National Drug Control Strategy (ONDCP) announced a $5 billion investment in increasing access to mental health care, preventing, and treating opioid addiction.

The high cost of opioid addiction and overdose is a major public health challenge, and more must be done to prevent these tragedies. Existing efforts to raise awareness of the dangers of fentanyl, make naloxone more widely available, and disrupt the flow of this drug into the United States can be accelerated by the emerging scientific breakthroughs that may lead to new drug formulations, fewer side effects, and vaccines for proactive protection.